NEA releases reading study; people not wearing enough hats

The National Endowment for the Arts (the other NEA, not the terrorist organization) released a big, important report yesterday, To Read or Not To Read, synthesizing over 40 studies to comprise "everything the federal government knows about reading." In an obligatory press-release second-graf block quote, NEA chair Dana Gioia tried to scare the bejesus out of all us slackers:

"The new NEA study is the first to bring together reliable, nationally representative data," said Gioia. "This study shows the startling declines, in how much and how well Americans read, that are adversely affecting this country's culture, economy, and civic life as well as our children's educational achievement."

The results, taken at face value, are indeed troubling. Literary reading as a voluntary activity has declined among young adults. Reading scores have "deteriorated" in the teen years, and while American employers are demanding better skills, today's high school graduates rank below Poland and Korea in proficiency. We're even behind Canada.

If you're not shocked and awed by that, the NEA has scary examples of cultural fallout on display. Still think it's cool not to read, kids? Well, which one of these bullet points would you want to fall under?

• 84% of Proficient readers voted in the 2000 presidential election, compared with 53% of Below-Basic readers.

• Only 3% of adult prisoners read at a Proficient level.

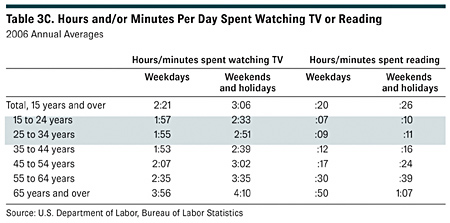

And what study of reading would be complete without a Vibram-soled kick or two at the still-twitching dead horse of television?

|

| From To Read or Not To Read (Research Report #47), courtesy of the National Endowment for the Arts. Of course, Roger Waters covered this in his 1992 album, Amused to Death. |

And yes, they have a full-page tinted call out in which they quote Neil Postman's Amusing Ourselves to Death. "We are now a culture whose information, ideas and epistemology are given form by television, not by the printed word. [...] They delude themselves who believe that television and print coexist, for coexistence implies parity. There is no parity here. Print is now merely a residual epistemology, and it will remain so, aided to some extent by the computer, and newspapers and magazines that are made to look like television screens."

The late Dr. Postman was a brilliant and incisive theorist, and I agree completely with him about television. But it is worth remembering that he wrote those words in 1985, two years before the first Hypertext conference and six years before the Web was invented to share scientific research papers. Now admittedly, not every minute spent on the Web these days is with sites like Wikipedia or Project Gutenberg, but text is still a dominant component.

And yet, despite the fact that the report was being released the same week Amazon announced Kindle, likely to be the first commercially viable e-book reader, nobody at the NEA seems to take online reading very seriously:

• Literary reading declined significantly in a period of rising Internet use. From 1997–2003, home Internet use soared 53 percentage points among 18- to 24- year-olds. By another estimate, the percentage of 18- to 29-year-olds with a home broadband connection climbed 25 points from 2005 to 2007.

A decline in literary reading for pleasure. Is this any surprise, given the grinding, meathook insistence on testing that "accountability" has driven into our school systems? I'm shocked. Shocked, I say. Let's make those kids read Fahrenheit 451. That will fix things. And what are Those Kids Today doing with all that bandwidth?

• 20% of their reading time is shared by TV-watching, video/computer game-playing, instant messaging, e-mailing or Web surfing.

There is no doubt that reading has been reconfigured by digital technology. As I have been arguing for years, the electronic text marks a departure as radical as the change from orality to literacy. But truly investigating the new is nowhere near as easy as lamenting the decline of the status quo. This NEA report is very old wine in a new bottle: Socrates made the same complaint about the new world of writing compared to the spoken rhetoric of which he was a master.

"[Writing] is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality." — Plato, Phaedrus

Assisting our children with the transition to digital literacy is not best accomplished by hand-wringing over the Way Things Used To Be. The NEA's proposed solution, called "The Big Read," aims to "restore reading to the center of American culture," by encouraging communities to read novels like "The Death of Ivan Illich" and "The Great Gatsby." Can you think of anything less likely to foster reading for pleasure than some government-sponsored program to make us appreciate dead 20th-century literature?

There is reading happening all over the Web, on blogs, wikis, e-mail, SMS, Twitter. More importantly, there is writing happening too, and reading-writing connections with a genuine audience that far outstrip anything available in the pure print age. That's where we should be applying our pedagogical shoulder to the wheel.

With mobile devices you have the whole world of open-source literature in your hand, wherever you are; I can sit in a coffee shop with my iPhone and call up Shakespeare, Plato, and Mark Twain. But I can also read Sheila Lennon, Eileen Spillane, and Kiersten Marek. Imagine a future where all citizens were part of a community dialogue, reading and writing into shared spaces that crossed over from schools to work to the public sphere. That would be a very Big Read indeed.

But it's always easier to focus on the familiar world of the past than try to comprehend something truly new and scary, and I guess we can't expect more from the government than the corporate executives lampooned by Monty Python in their final film...

[Large corporate boardroom filled with suited executives]

Exec #1: Item six on the agenda: "The Meaning of Life" Now uh, Harry, you've had some thoughts on this.

Exec #2: Yeah, I've had a team working on this over the past few weeks, and what we've come up with can be reduced to two fundamental concepts. One: People aren't wearing enough hats. Two: Matter is energy. In the universe there are many energy fields which we cannot normally perceive. Some energies have a spiritual source which act upon a person's soul. However, this "soul" does not exist ab initio as orthodox Christianity teaches; it has to be brought into existence by a process of guided self-observation. However, this is rarely achieved owing to man's unique ability to be distracted from spiritual matters by everyday trivia.

Exec #3: What was that about hats again?

Exec #2: Oh, Uh... people aren't wearing enough.

— Monty Python's Meaning of Life, via IMDB

Full disclosure: I am a huge fan of Neil Postman. He was my teacher and dissertation advisor, and he told me many times that I was crazy. But he meant it in a nice way.

Comments

nakaplan

Fri, 11/30/2007 - 12:00pm

Permalink

Yes, and distorted data to boot

It's good to take on the NEA for its misguided ideas about reading and its future, but it is also a good idea, I think, to debunk the foundations of its argument. Most responses to the report have more or less accepted the NEA's claim that the reading proficiency of 17 year olds and of adults is declining. Indeed, the whole argument rests on that "conclusion." So what if people, including teens, are not reading as many books in their leisure time as we think they ought or as we think they did years ago, if there is no measurable negative effect?

So, here's the skinny on the data: the NEA has done what Bush-league agencies always do -- lie with statistics. The first exhibit is this graph:

The NEA's version shows data from 1984 through 2004 and places each data point on the grid as if the time intervals between the data points were regular. They're not. The NCES graph shows the whole series, from 1971 through 2004 and spaces the points to correspond to the accurate time intervals between tests. The result? The NCES series shows that the average reading proficiency score of 17 year olds in 2004 is EXACTLY the same as the average reading proficiency when testing began in 1971. There was, apparently, some improvement in scores from 1984 through 1992 -- an entirely unexplained phenomenon -- but scores returned to their historic averages thereafter.

Moreover, the decline pictured in the NEA graph looks precipitous, but that's simply because of the spatial distortion. The NCES graph shows the proper slope of the line and also shows that the downward slope from 1999 to 2004 (a five-year interval) is pretty much the precise reverse of the upward slope from 1980 to 1984 (a four-year interval). Although the changes in scores are statistically significant, neither slope is especially steep.

As for the measures of adult proficiency, the story is much the same: cherry-picked and misleading data. In this case the NEA drew its information from the NCES report about the latest National Assessment of Adult Literacy, called "Literacy in Everyday Life" (http://nces.ed.gov/Pubs2007/2007480.pdf). That report asserts that "between 1992 and 2003, there were no statistically significant changes in average prose ... literacy for the total population ages 16 and older..." (p. iv).

So what does NEA do? Uses the details of the data in a misleading way. The NCES report notes that reading proficiency scores declined for all educational attainment levels above high school but goes on to explain, again, that there has been NO STATISTICALLY SIGNIFICANT change in reading proficiency among all adults. A bit of a paradox, no? Yes. And explained in the NCES report this way:

Among other things, the NAAL report finds that various demographic factors, especially an adult's first language and the age at which that person learned English, have significant effects on proficiency with literacy in English. A quick look at changes in population over the same period provides a reasonable hypothesis to explain the NAAL data. Over the period measured in the latest report, the US has experienced large increases in immigrant populations. For example, in 1990, 7.9% of the total US population were foreign born; in 2000, the 11.1% of the population were immigrants. The overwhelming majority of foreign born residents of the US (97% of naturlized citizens and 84% of all other foreign born residents) are adults. Such changes in the make-up of the population might have important effects on the data.

Bottom line: don't trust the data in the NEA report. And don't trust the conclusions drawn from the data.

Meanwhile, let's think better and more broadly about reading (and who is wearing not enough, or perhaps too many, hats)!

John McDaid

Fri, 11/30/2007 - 1:25pm

Permalink

Thanks!

Hi, nakaplan...

Welcome to this little corner of the blogosphere, and thank you for your most elegant vivisection of the NEA report. I should have known better than to just trust the charts within their document without asking the classic Tufte "compared to what" question.

BTW — my hypothesis for the 1984-1992 increase in reading skill bubble, I'm going to bet Sesame Street is at least partly responsible.

Thanks for a most informative post.

Cheers.

-j