The following is reproduced, by request and permission, from the blog of Prof. Lance Strate of Fordham University.

Children are the Living Messages We Send to a Time We Will Not See

Lance Strate, Time Passing

I want to ask you to help me correct an inaccuracy out here on the net, an inaccuracy that amounts to an injustice. Here’s the story:

|

| The Disappearance of Childhood |

Neil Postman wrote, “Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see.” This is the first sentence that opens his book, The Disappearance of Childhood, which was originally published in 1982 by Delacorte Press.

I can remember being a young doctoral student in the old media ecology program at NYU, I was just 22 when I started there in 1980, and seeing Neil writing the book with a black felt tip pen on yellow legal pads.

|

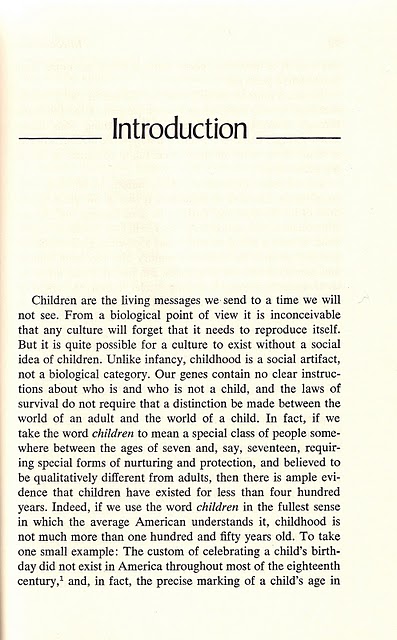

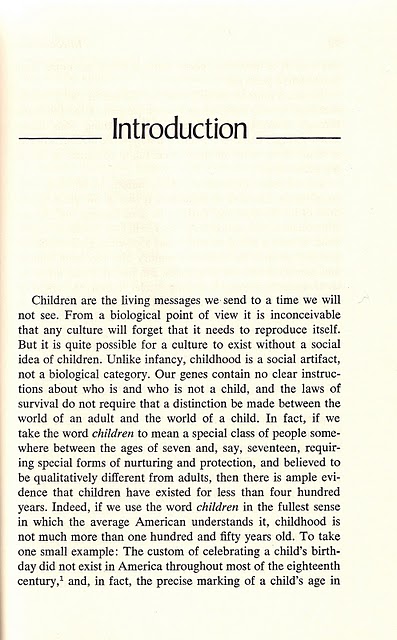

| Postman's introduction, where "Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see" is clearly visible. |

Neil Postman wrote “Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see” as the first sentence of the Introduction to that book, appearing on p. xi. Here, take a look:

The Disappearance of Childhood was the second of Postman's major works providing a critical analysis of television's influence on culture. It was preceded by Teaching as a Conserving Activity, and followed by Amusing Ourselves to Death. And if you find Postman's media ecology scholarship at all interesting and valuable, and especially if you've read Amusing Ourselves to Death and you haven't read The Disappearance of Childhood, then you will find The Disappearance of Childhood to be a delightful companion piece, a well-crafted extended essay, and important work of cultural criticism.

Postman begins by writing that “children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see,” because he was writing about communication, which involves the sending of messages through a channel to a receiver. In the case of messages sent to the future, the receiver may be unknown to us, but the basic idea still applies. This view originates in the post-war era with the Shannon-Weaver Model:

|

| The Shannon-Weaver model |

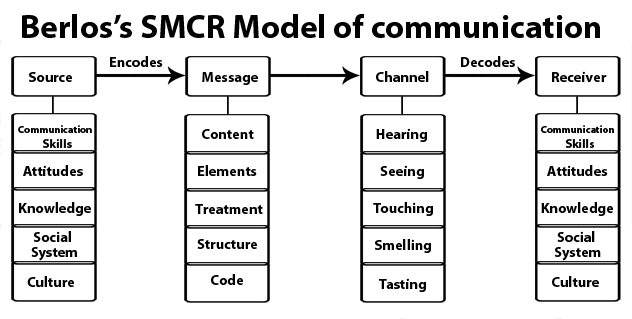

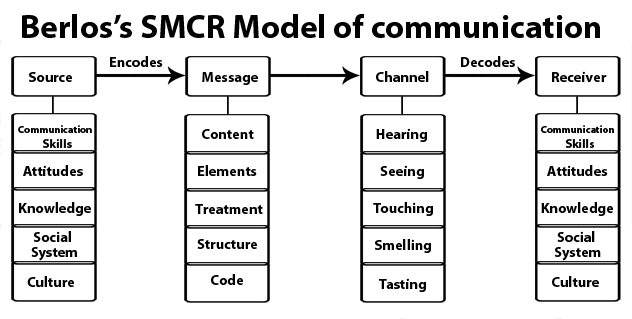

The Shannon-Weaver Model was modified by communication theorist David Berlo circa 1960:

|

| The Berlos "SMCR" model |

But the important point is that Postman was writing about communication, and thinking about children, and childhood, in terms of communication. The idea that children are our legacy, a way of projecting something of ourselves into the future, is a time-honored, traditional notion. But thinking of children as messages, as part of the process of communication, is a relatively new orientation.

And as any good media ecology scholar knows, in 1964 Marshall McLuhan declared that "the medium is the message," by which he meant (among other things) that the messages we send are influenced in significant ways by the medium that we use to create and send them And The Disappearance of Childhood is all about how children as messages are influenced by the media that they use, and that we use to prepare our children to carry on for us in the future. And it is about how childhood is a message that is influenced by the medium that we use to create it.

Yes, create it, because childhood is a cultural construct (albeit one based on an underlying biological reality), a message we send to ourselves about biological and social reproduction. In print culture, children came to be seen as special and innocent, and in need of extended protection as they were cloistered away in schools, while television culture has returned us in some ways to a view of childhood that does not allow for much distinction between children and adults, hence the title The Disappearance of Childhood (which also signals the disappearance of adulthood).

But you really have to read the book to get Postman's argument. And I only provide this cursory summary to underline the fact that Postman's quote, “children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see,” with its particular emphasis on children and communication, originated out of a very specific set of circumstances, and its meaning is quite clear in that context. But it also has a wonderfully poetic quality, evocative and compelling, and works quite well standing alone. Some might even be fooled into thinking it is some kind of ancient proverb, despite its clearly contemporary sensibility.

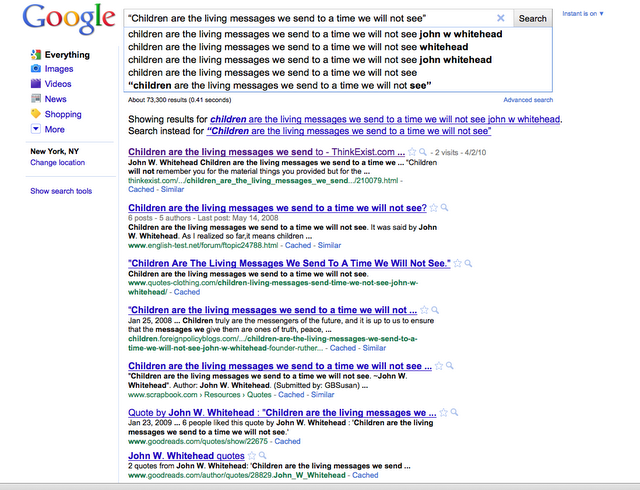

“Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see” is Neil Postman's most famous quote. So what's the problem, you might ask? And I'm glad you did. The problem is that when you Google the quote nowadays, you get something like this:

|

| Google hits for "Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see" |

|

| Whitehead's book |

How did this come to be, you might ask? And I'm glad you did. You see, this John W. Whitehead wrote a book entitled, ironically enough, The Stealing of America.

And this book was published in 1983, a year after The Disappearance of Childhood. [... images of copyright pages removed to save space; see Prof. Strate's blog]

And just to dispel any lingering doubts, here is p. 68 of Whitehead's book, where he specifically cites Postman.

The Disappearance of Childhood also is included in the list of references that appear at the end of the book.

|

| Whitehead's unquoted string. |

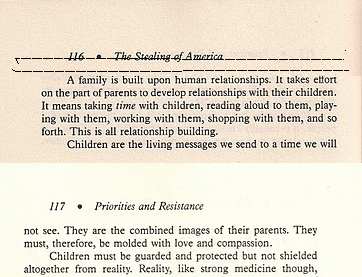

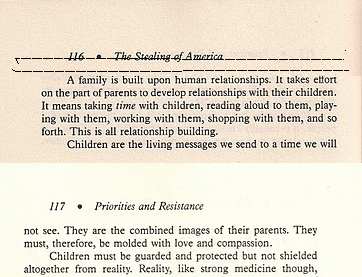

So, are you ready now? Ok, here is how Postman's quote appears in Whitehead's book, starting on the bottom of p. 116 and continuing on to p. 117:

Ah ha, you may be saying! Caught red-handed! Well, the problem is that the circles that Whitehead travels in, and the readership that he picks up, is quite different from those associated with Postman. So who knew? It would have been quite the coincidence to come across it back in the 80s, or even the 90s. But, the quote being so poetic and memorable, it got picked up from Whitehead's book, and reproduced all over the place with the wrong attribution. It appears in some baby book, which probably amplified the error significantly.

Who is this guy, anyway, you might ask? Well, you can read about him on this page from the Rutherford Institute website: About John W. Whitehead. And you can read about the Rutherford Institute on their Wikipedia entry: Rutherford Institute.

Not that it matters much. I am writing this, and asking for your help, not to cast blame or level accusations. Postman was certainly the easygoing, forgiving sort of person who would not have made a big issue out of this. But speaking for those of us who honor his memory, and who believe in credit where credit is due, we would like to set the record straight.

The problem is that it is very hard to set the record straight on the web. It is very hard to get the content of websites changed. You can send a message, but it may be that the site is no longer active, or no longer actively supervised, or it may be that the individuals associated with the site just don't want to be bothered, or just don't care. Believe me, attempts have been made, and met with no success.

But, the main thing to do when dealing with problems like this is to accentuate the positive (see my previous post, Digital Damage Control). So, I am asking you to help to get the word out on the web, anyway that you can.

Please feel free to repost all or part of this entry on your own blog or site or elsewhere on the web. Or write your own post about this situation, using any part of this post that you care to, it is entirely open and available for copying and revising.

If you do post this or a similar message anywhere else, let me know, and I will add an acknowledgment and link at the end of this post.

And/or, please link to this post.

And/or, spread the word and the link via Twitter, Facebook, and other social media. If you tweet, Neil Postman wrote, “Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see,” that will be less than 50 characters, so you can add, please retweet, include a link to this post or another one, and/or note that we want to remedy an injustice.

I ask that you please help me to get this particular message out there, get more positive posts and listings out there, and at least we can start to set the record straight.

Neil Postman did not live to see this time of Google and social media, but today, March 8th, 2011, is the 80th anniversary of his birth, and if he were still with us, he would joke about how what we are doing here is launching Operation Childhood, and probably ask if there wasn't some better way for us to spend our time, like reading a good book. But deep down, he would be very much appreciative of the messages that we now can send on his behalf.

So I ask you to be a living message now, and for the future.

Full disclosure: Neil Postman was my dissertation advisor, and one of the few people who believed me, in 1987, when I said that this thing called "hypertext" was a completely new communication paradigm. I have read "The Disappearance of Childhood," and can personally attest that this quote rightly belongs to Neil.